For large patches of his later career Heinz Edelmann focused on quickly producing posters for arts events and series productions: these typically made use of a fairly regularized typographic template for information, and wild, allusive but enigmatic illustrations. For one season in the mid-1980s, he worked with the Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus theater, playing off the plays’ angsty plotlines with evocatively deformed bodies. For their production of Cabaret, Edelmann distills its atmosphere of the fading flappers in the poltical climate of the Weimar years and arrives at a Betty Boop-esque figure with a Hitlerized hairstyle.

As far as I can figure it, this is the plot of Totenfloss, according to Die Ziet (via Rowohlt Theater Verlag):

A country which is uninhabitable, it looks like a foreign planet, but all traces and rubble prove that this was once planet Earth. The ruler over this undead kingdom of the banished and contaminated is a monstrous being called Checker, half-human, half-animal. He obsessively examines his own body all the time for the level of poisoning and even his speech is a hideous mutation. Somewhere on their way to the Rhine, these vagrants [Checker, Itai and Bjuti traveling on the titular raft] come across an old man called Cuckoo, “one from the nineteen hundreds” who has survived the great catastrophe. He has also saved language from the apocalypse. His ceremonious High German and Old German is strangely dissonant in comparison to the “rubble German” of later generations. Cuckoo speaks and enthuses about the old, beautiful green earth (…) but Checker only laughs mockingly at this strangely sentimental old man’s songs of peace and catches flies mid-air and gobbles them up…

This play sounds vaguely Dickensian: it takes place in Munich, Octoberfest 1929. Kasimir has just lost his job, and subsequently gets into a fight with his fianceé Karoline. Amid humorous episodes and slapstick, the couple reconcile and split up repeatedly, in the process encountering everyone from bon vivant gentlemen to petty thieves.

Pirandello’s 1920 play has a wacky conceit that I would hazard is not especially well articulated in this poster. The plot, according to Wikipedia:

A talented actor and historian falls off his horse in a historical pageant while playing the role of Henry IV. When he comes to, he believes himself to be Henry. For the next twenty years his nephew, Count de Nolli, funds an elaborate hoax in a remote villa, where actors play the roles of Henry’s privy councillors and simulate the 11th century court. On request from his dying mother de Nolli brings a Doctor referred to as the latest in a succession to try and cure Henry (whose real name, if it is not Henry, is never mentioned).

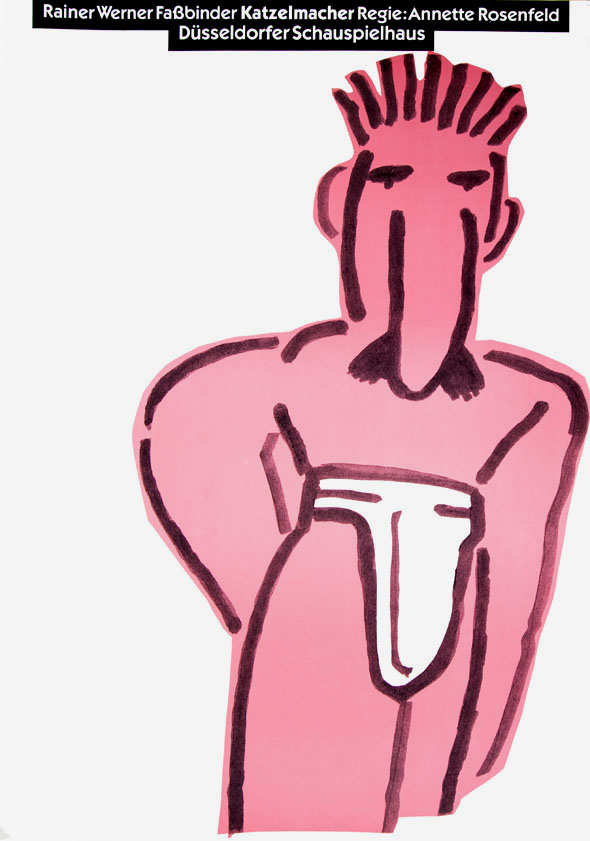

Fassbinder adapted his play into his first film, in 1969. It predicted much of what he would become known for: dexterously running an ambiguous social critique underneath a Douglas Sirk-style melodrama. The word “Katzelmacher” is a Bavarian slur for foreign laborers with, apparently, sexual connotations. The plot is similar to Fellini’s second movie, I Vitelloni: both about the frustrations of idlers in small towns in postwar Europe. Edelmann’s caricature, with its underwear and oversized schnozz competing for space, recapitulates Gogol’s phallic nose as a metaphor for the play’s conflicted sexual tension.

This post also appears on our Picturebox blog: Beth, myself, and the publisher Dan Nadel will be highlighting items from our collections that resonate with their focus on comic art, illustration, and historic visual styles. More on Picturebox available at their new website.