I’ve really been getting into “folk” textiles lately, thanks mostly to the rather unscholarly examples found on eBay. A few months ago, you see — after a ceiling collapse subsequent to a visit by Hurricane Irene — my couch was rather a rain-damaged eyesore. And when I finally did replace it, it was with the trepidation that accompanies buying large pieces of furniture knowing you’ll have to hitchhike them back to your apartment. Anyway — to cut to the chase here — the new couch is gloriously large and contemporary. A big improvement to be sure. But it rattles me with its monolithic boringness: off-white microweave, completely rectilinear; really almost inhumanly neutral — full of slick modern touches but without a Danish teak tapered leg to stand on.

So I proceded to cover it up with as much a motley of Armenian, Malian, and Azerbaijani textiles as I can afford. In doing so I happened to be going through the 1972 season at the Visual Arts Gallery and reignited my curiosity about the Navajo Weaving show, which seemed to stir something in the artists and critics of the time. The gallery file is now, for various reasons, considerably more complete than when I flipped through a year ago. One page of handwritten notes by the curator, Emily Wasserman, appears rather off-handedly to account for the show’s origin:

11/12/72 — Consented to do exhibition replacing Sam Gilliam 3/6 – 3/30/72: notify of topic in 2 weeks. 1/17/72 — Indian rugs.

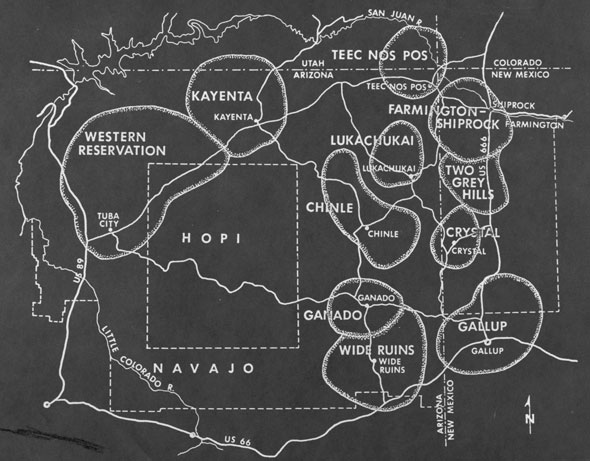

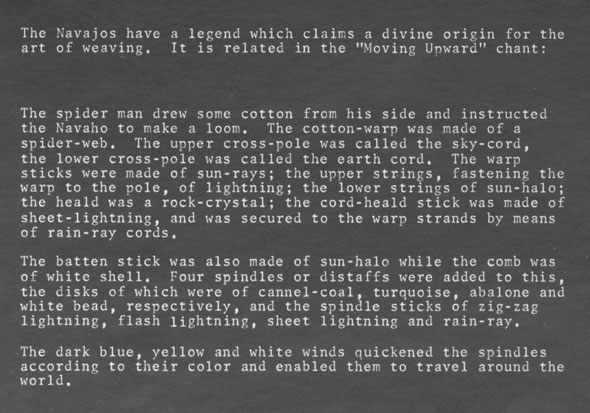

The next lines are about one dry cleaner’s rate for cleaning Navajo rugs (40c / sqft) and a consideration of PMS 448 (a dark brown) for the walls. Wasserman credits John Holstein for lending many pieces and helping with show’s background (including references to The Navajo and his Blanket, something of a classic text in the field written by Uriah Hollister and published in 1903). Her press release integrates this historical material with both a sociopolitical context and an art-historical one, stressing the material changes that altered the practice of Navajo weaving over time, “in the midst of the devastating acculturation process which all the North American Indian tribes underwent.” Navajo weaving, like many American folk art forms, was “an odd marriage” between native and imposed cultures — in this case between “the use of an upright, stationary loom by the Pueblo peoples and the introduction of European fleece sheep.”

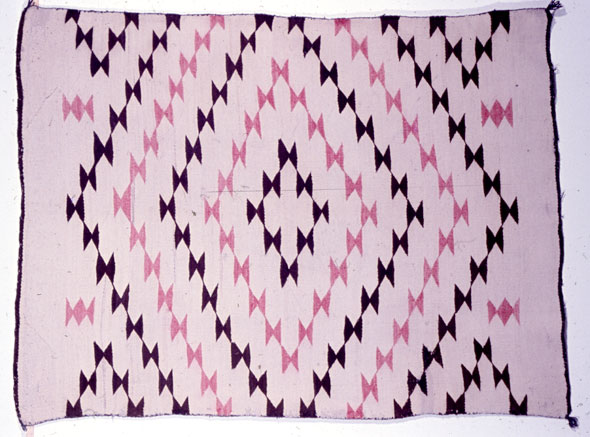

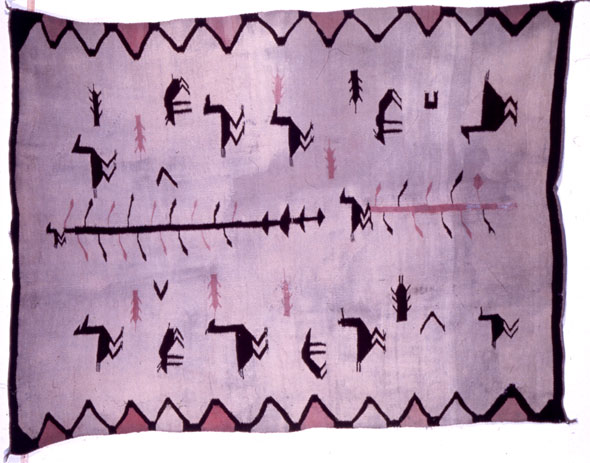

The textiles, originally produced for use as blankets, eventually were commodified by Europeans to the extent that their production moved in the direction of ornament, and they were, no doubt due to the colorful ornamental weavings more familiar to Europeans, mislabeled “rugs.”

Wasserman notes that “the variety, vigor of pattern and color, and the range of invention displayed in these beautiful textiles are a rich source of graphic design to be confronted by students of the arts today.” But what seemed to strike everyone — especially the contemporary reviewers — is not what they suggested to graphic designers, but to painters. And, after all, look who lent these:

Frank Stella and Kenneth Noland sent several each, joining the company of weavings loaned by Larry Zox, John Griefen and gallerist Donald Droll. One bit of correspondence suggests Jules Olitski spoke about contributing but it didn’t come to pass.

I guess what interests me in part about all this is that at this moment — 1972 — when you might suppose (or be supposed to suppose) that Minimalism and attendent conceptual arts were dethroning Abstract Expressionism, here you find some of their leading practitioners neatly coinciding in their triumph of an art that exhibits some of the best traits of each. (Namely, something like intense saturation and the indexical mark as well as studious repetition and process or collaboration.) And, you could also argue, Minimalism and Abstract Expressionism were at that time facing precisely the transformative quality of commodification that originally removed the Navajo blanket from the body and put it on the wall.

See also: the poster for the exhibition, posted here.